The Sweepback Controversy

Part of The Hall Bulldog Project — documenting Bob Hall's 1932 Thompson Trophy racer.

Explore the Project →One of the most debated aspects of the Hall Bulldog’s design is whether its wings featured sweepback. Some historians have argued that photographs appearing to show swept wings are merely optical illusions caused by camera distortion. Others point to period documentation and Bob Hall’s own statements confirming 5 degrees of sweepback.

After years of research, including 3D model matching and shadow analysis, the evidence strongly supports the existence of sweepback in the original aircraft.

The Rolling Shutter Argument

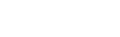

Critics of the sweepback theory have pointed to the limitations of 1930s camera technology. Cameras of the era used focal-plane shutters that exposed the film progressively rather than all at once. When photographing fast-moving objects, this could create distortion—most famously seen in photographs of racing cars where the wheels appear oval-shaped and the entire vehicle seems to lean forward.

Rolling shutter distortion in a period photograph. Note the oval wheels and forward lean—a stylistic effect later adopted by animators to convey speed.

The argument goes that photographs of the Hall Bulldog in flight showing apparent sweepback are simply artifacts of this same distortion. However, this explanation has several problems:

-

Multiple angles: The Bulldog was photographed from many different angles relative to its direction of travel. Rolling shutter distortion is directional—it would not consistently produce the appearance of sweepback from all viewing angles.

-

Ground photographs: Many photographs showing the wing planform were taken with the aircraft stationary on the ground, where rolling shutter effects would not apply.

-

Consistent geometry: The apparent sweep angle is consistent across photographs taken at different times, by different photographers, under different conditions.

3D Model Analysis

Perhaps the most compelling evidence comes from matching period photographs against accurate 3D models. Two detailed models of the Hall Bulldog exist: one by Vern Clements incorporating 5 degrees of sweepback, and one by Steve Kerka without sweepback.

When a period photograph of the Bulldog in knife-edge flight is compared against rendered views from these models, the results are striking.

Period flight photo compared with Vern Clements’ 3D model featuring swept wings. The wing geometry matches closely.

The same flight photo compared with Steve Kerka’s 3D model without sweepback. Note how the straight wing does not match the photograph.

The Clements model—with its swept wings—matches the period photograph far more closely than the Kerka model. This analysis was performed by carefully matching the camera angle, focal length, and aircraft attitude between the 3D render and the original photograph.

In-Flight Photographic Evidence

I’ve collected these film frames and still photographs of the Bulldog in flight as further evidence of the wing sweepback. These images, captured from various angles during the 1932 racing season, consistently show the distinctive swept wing planform.

The Bulldog in a steep bank, viewed from below. The wing planform clearly shows the swept leading edge.

The Bulldog rounding a pylon at Cleveland. Race number 6 is clearly visible on the tail.

Multiple racers in flight at Cleveland. The Bulldog’s swept wings are visible among the other aircraft.

Race action at Cleveland with spectators watching from below.

Film frame capture showing race action. The Bulldog’s swept wing is visible.

Multiple aircraft in race action at Cleveland, 1932.

These photographs provide independent confirmation of the wing geometry visible in the 3D model comparisons above.

Wing Shadow Evidence

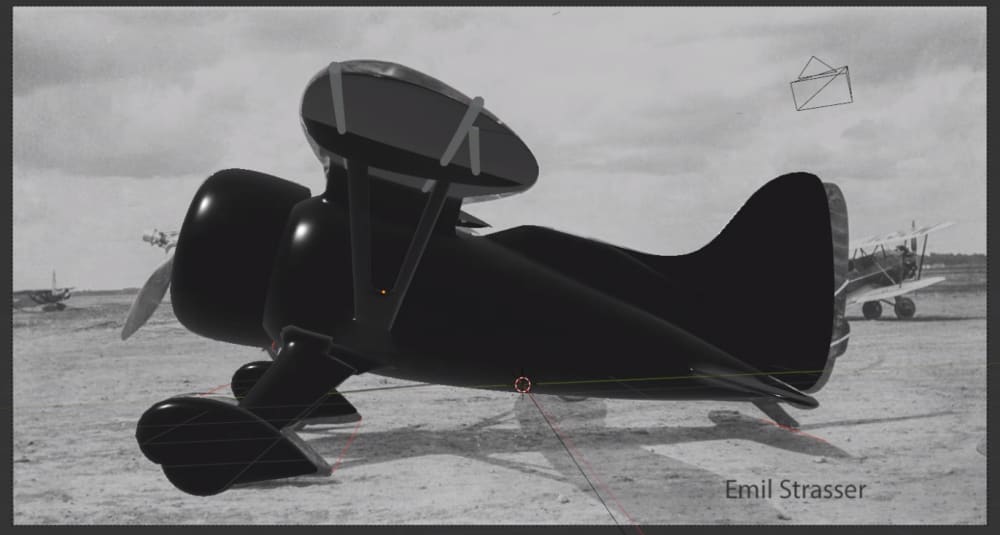

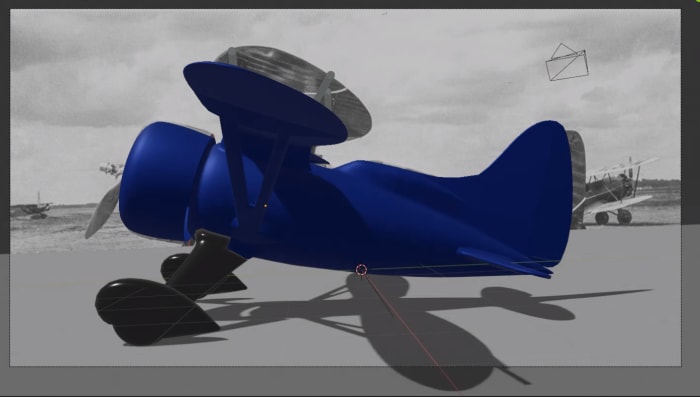

Another line of evidence comes from analyzing the shadow cast by the wing onto the fuselage. In a photograph taken by Emil Strasser, the wing shadow is clearly visible on the side of the fuselage. By recreating the lighting conditions in 3D software, we can compare what shadow a swept wing would cast versus a straight wing.

Emil Strasser photograph showing the wing shadow cast on the Hall Bulldog’s fuselage.

Clements model (swept wings): Shadow matches the photograph.

Kerka model (straight wings): Shadow does not match.

Once again, the swept-wing model produces a shadow that closely matches the period photograph, while the straight-wing model does not.

The Sweepback Enigma

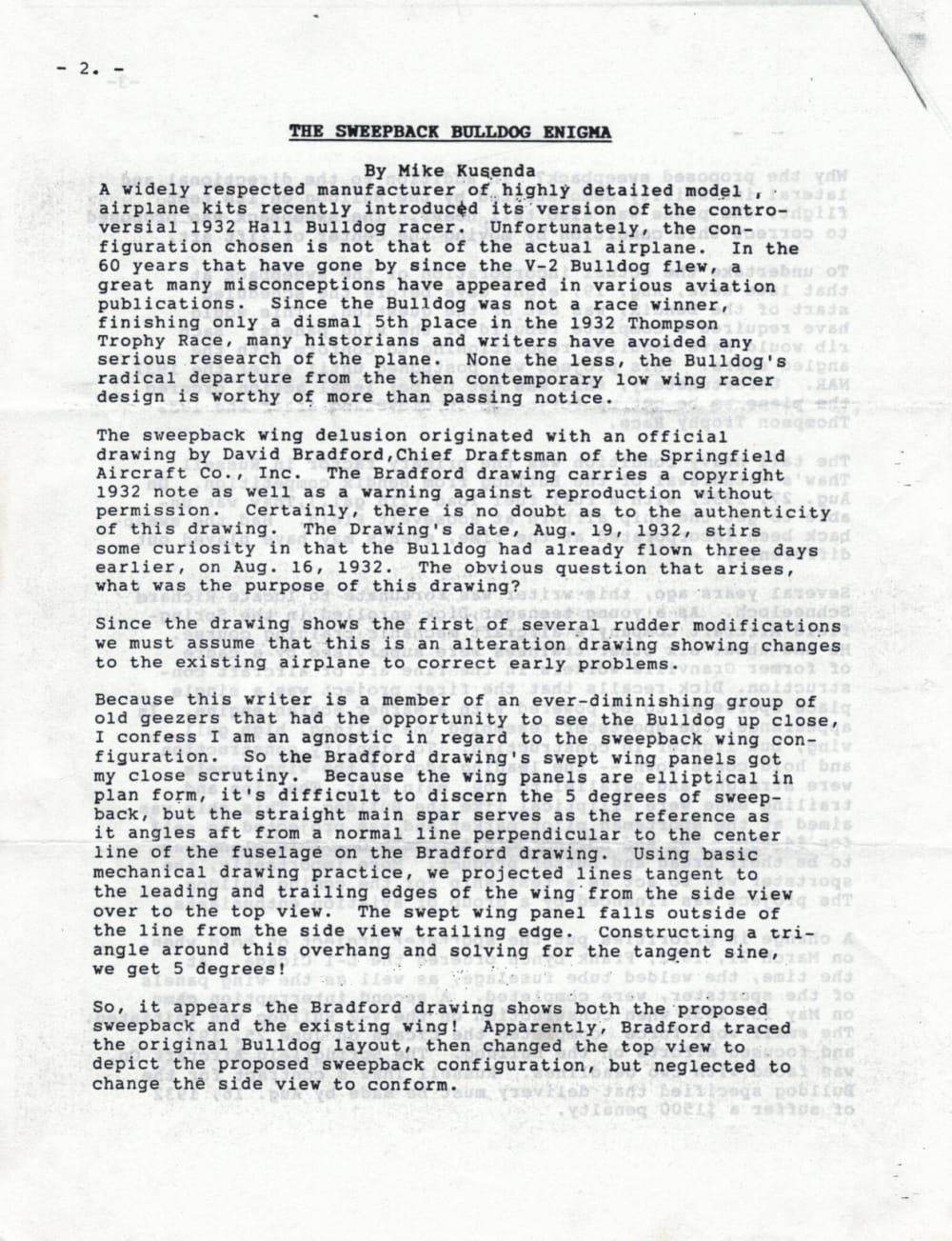

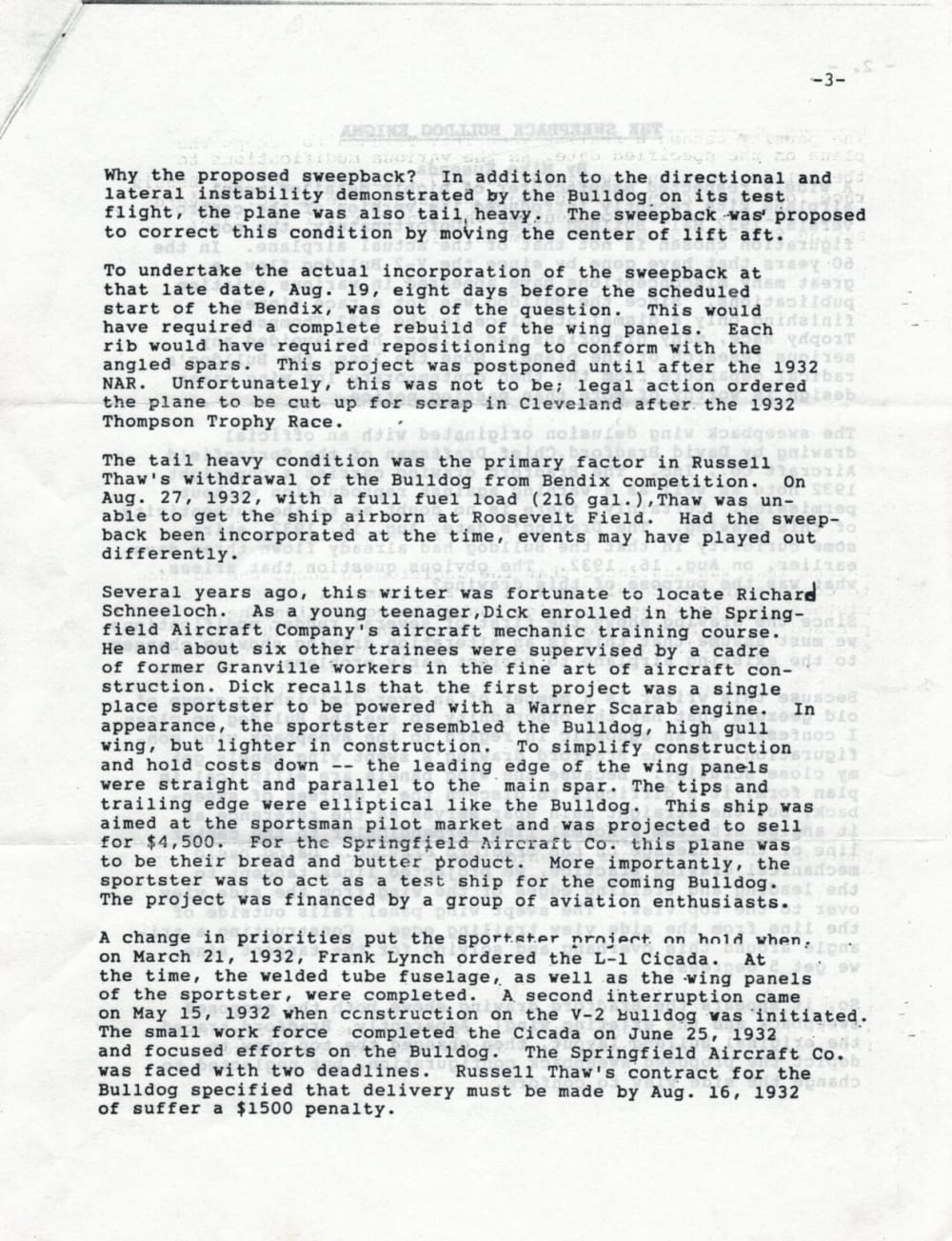

Aviation historian Mike Kusenda, who contributed significantly to Hall Bulldog research, wrote an article titled “The Sweepback Bulldog Enigma” arguing against the existence of sweepback. His analysis deserves serious consideration, even as we present evidence to the contrary.

Download Original PDF

(4.6 MB)Kusenda’s key arguments include:

-

The Bradford drawing: He notes that David Bradford’s official drawing, dated August 19, 1932 (three days after the Bulldog’s first flight), shows modifications to the rudder. Kusenda argues this suggests the sweepback shown in the drawing was a proposed change, not the as-built configuration.

-

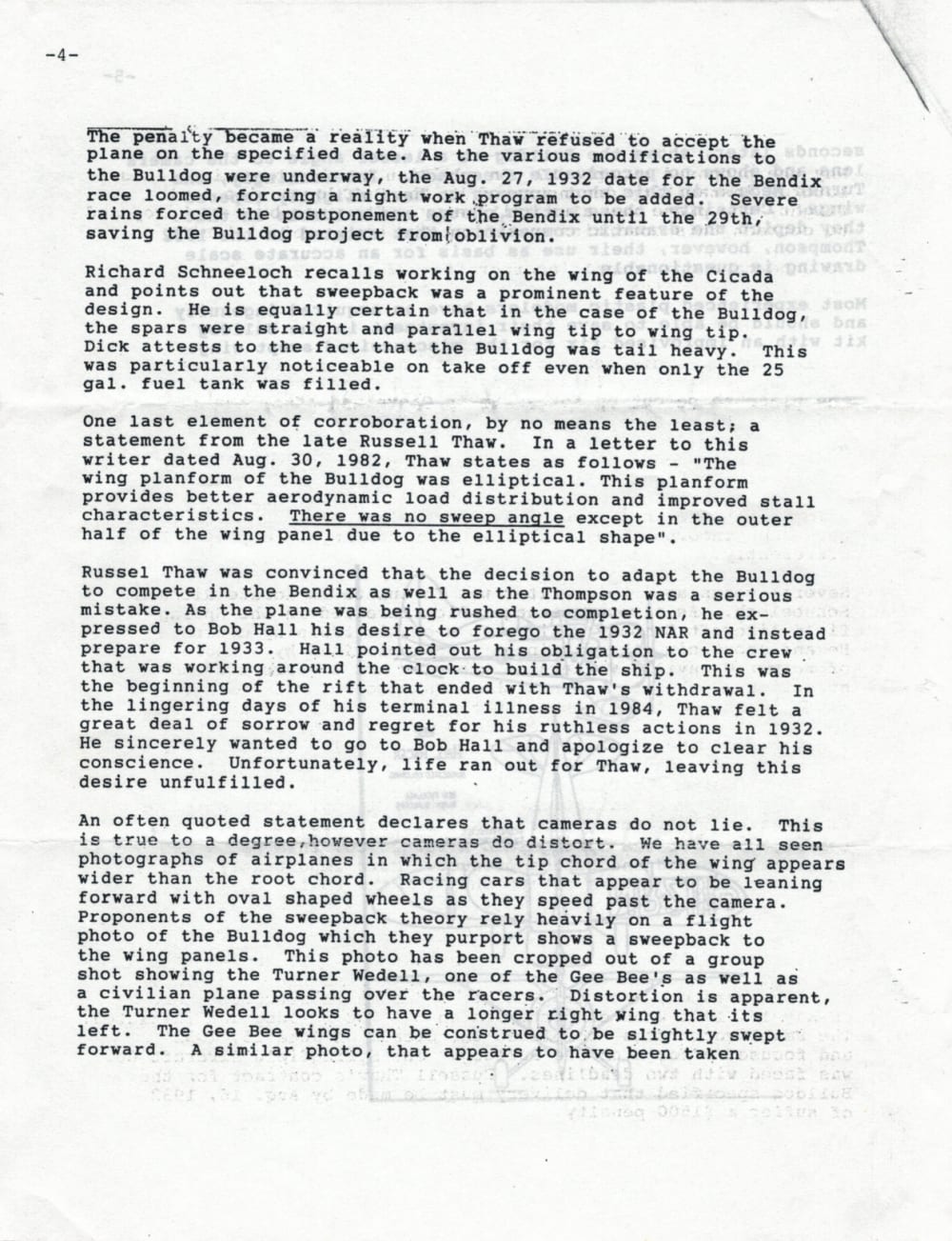

Witness testimony: Richard Schneeloch, who worked on the Cicada (a smaller aircraft built by Springfield Aircraft Co.), recalled that the Bulldog’s wing spars were “straight and parallel from tip to tip.”

-

Russell Thaw’s letter: In a 1982 letter, Thaw wrote that “the wing planform of the Bulldog was elliptical” with “no sweep angle except in the outer half of the wing panel due to the elliptical shape.”

-

Camera distortion: Kusenda points to a cropped flight photo showing the Bulldog alongside other aircraft, noting apparent distortion in the other planes’ wings as evidence that the Bulldog’s apparent sweep is also an artifact.

Page 1: Introduction and analysis of the Bradford drawing

Page 2: Discussion of the proposed sweepback and Springfield Aircraft’s Cicada project

Page 3: Witness accounts from Richard Schneeloch and Russell Thaw, plus analysis of flight photographs

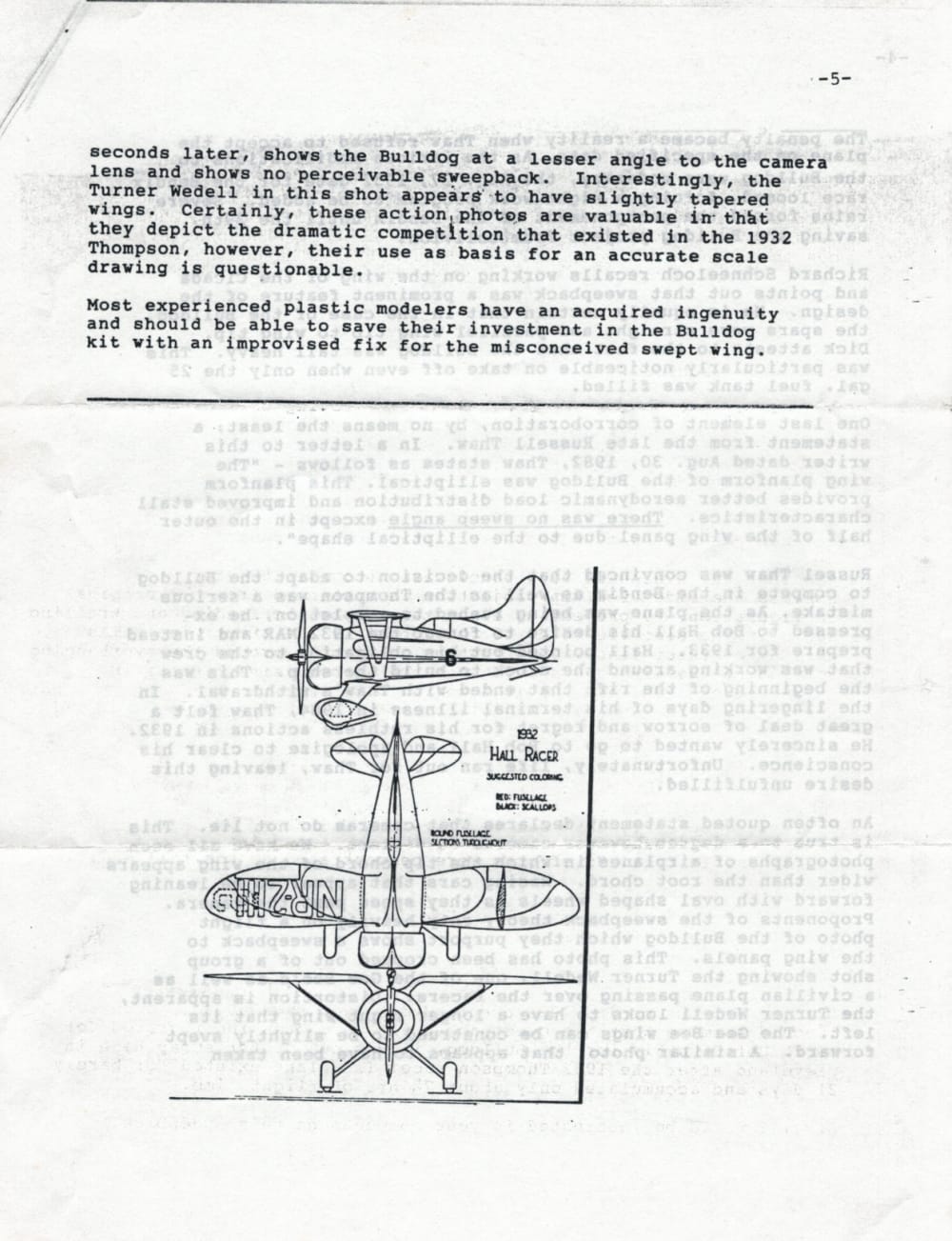

Page 4: Conclusion and three-view drawing of the Hall Bulldog

Examining the Counter-Arguments

While Kusenda’s research is valuable, several of his arguments warrant closer examination:

The Bradford Drawing

Kusenda assumes the Bradford drawing shows proposed modifications rather than the as-built configuration. However, there are no known drawings from this period that do not show sweepback. If sweepback was merely proposed, we would expect to find drawings of the original straight-wing design—yet none have surfaced.

Witness Testimony

Richard Schneeloch’s recollection that the spars were “straight and parallel” refers to his work on the Cicada, not the Bulldog. The Cicada was a smaller, simpler aircraft designed for the sportsman pilot market, with a different wing planform than the racing Bulldog. Kusenda himself notes that the Cicada’s “leading edge of the wing panels were straight and parallel to the main spar.”

Russell Thaw’s Statement

Thaw’s description that there was “no sweep angle except in the outer half of the wing panel due to the elliptical shape” could actually be interpreted as confirming sweepback. The Bradford drawing shows sweepback concentrated in the outer portion of the wing—consistent with Thaw’s description. The elliptical planform would naturally produce apparent sweep in the outer panels.

Race Placement

A minor factual note: Kusenda states the Bulldog finished “only a dismal 5th place” in the 1932 Thompson Trophy Race. In fact, the Bulldog finished sixth. While a small error, it suggests the document may not have received rigorous fact-checking.

The Flight Photo Analysis

Kusenda’s argument about camera distortion in the group flight photo conflates different phenomena. The photo he references—showing the Bulldog alongside Turner Wedell and Gee Bee racers—does show some distortion, but this shearing effect affects the entire image uniformly. It does not selectively make one aircraft’s wings appear swept while leaving others straight.

Furthermore, the knife-edge flight photograph used in our 3D analysis appears to be a different image than the one Kusenda describes. The Hall Bulldog was photographed in flight multiple times from various angles, and the consistent appearance of sweepback across these images argues against camera distortion as the explanation.

Bob Hall’s Own Words

Perhaps most significantly, Bob Hall himself documented the sweepback on multiple occasions. His written statements confirm 5 degrees of sweep in the wing design. No evidence has emerged suggesting Hall was confused about this fundamental aspect of his own aircraft’s design.

The sweepback served an aerodynamic purpose: the Bulldog was tail-heavy, and moving the center of lift aft through sweepback helped address this balance issue. This is consistent with the aircraft’s known handling characteristics and the modifications made throughout its brief racing career.

Conclusion

The weight of evidence strongly supports the existence of sweepback in the Hall Bulldog’s wing design:

- Period documentation: All known drawings from 1932 show sweepback

- Designer’s statements: Bob Hall confirmed 5 degrees of sweepback in writing

- 3D model matching: Only the swept-wing model accurately matches period photographs

- Wing shadow analysis: The shadow geometry confirms a swept wing planform

- Multiple photographs: Consistent apparent sweepback across many images from different angles and conditions

While historians like Mike Kusenda have raised thoughtful objections, the photographic and documentary evidence—combined with modern analysis techniques—makes a compelling case that the Hall Bulldog did indeed feature swept wings.

The controversy itself is a reminder of how difficult it can be to reconstruct the exact details of historic aircraft, especially one that existed for such a brief period and left behind limited documentation. We owe a debt to researchers like Kusenda who have worked to preserve what records do exist, even when we may reach different conclusions from the same evidence.