Robert 'Bob' Hall: From Gee Bee to Grumman

Part of The Hall Bulldog Project — documenting Bob Hall's 1932 Thompson Trophy racer.

Explore the Project →Robert Leicester Hall (1905–1991) was one of aviation’s most accomplished and least celebrated figures. In a career spanning four decades, he designed aircraft that dominated air racing in the early 1930s and then created the fighters and torpedo bombers that helped win World War II. Throughout it all, he maintained a principle that defined his character: he would never ask another pilot to fly an aircraft he hadn’t tested himself.

Early Life and Education

Bob Hall was born on November 21, 1905, in Taunton, Massachusetts. His fascination with flight began early—at age nine, he built a powered model aircraft. This childhood passion would shape his entire career.

Hall began his engineering studies at Harvard in 1922, later transferring to the University of Michigan where he graduated in 1927 with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. He financed his education through a variety of odd jobs: bellhop, waiter, and summer road construction work.

First Jobs: Fairchild and Skyways (1927–1929)

Fresh out of college, Hall joined Fairchild Airplane Manufacturing Company as a draftsman. He quickly proved himself and was promoted to stress analyst, gaining invaluable experience in aircraft structural design.

In 1929, Hall briefly worked for Skyways Inc., where he designed an amphibian hull. This experience with different aircraft types would serve him well in his next position.

The Granville Brothers Era (1929–1931)

The Granville Brothers Aircraft team. Hall served as Chief Engineer during the company’s most successful period.

In 1929, Hall joined Granville Brothers Aircraft in Springfield, Massachusetts, as both Chief Engineer and test pilot. His first design there was the Model A biplane, followed by a succession of increasingly advanced aircraft—Models B, C, D, and E—each building on lessons learned from the last.

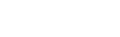

But it was the racing aircraft that would make history. Hall designed what would become the most famous—and infamous—racing aircraft of the golden age: the Gee Bee series. His masterpiece was the Gee Bee Model Z, nicknamed the “City of Springfield,” which was completed in just 30 days.

Bob Hall poses with the Gee Bee Z “City of Springfield”

The Model Z was a radical design—essentially a massive engine with the smallest possible airframe wrapped around it. On September 5, 1931, Hall himself flew the Gee Bee Z to victory in the General Tire and Rubber Trophy Race at the National Air Races. The next day, Lowell Bayles flew the aircraft to victory in the free-for-all event, cementing the Gee Bee’s dominance.

Just weeks later, on December 5, 1931, Bayles set a new world landplane speed record of 267.34 mph in the Model Z. Tragically, he was killed the same day attempting to break his own record when a fuel cap came loose and struck the aircraft’s tail.

Hall with the Gee Bee Model D Speedster

Hall also competed in the 1931 Thompson Trophy Race, piloting a Gee Bee Model Y (race number 54) to a fourth-place finish at 201.25 mph.

Despite this success, a disagreement with the Granville Brothers led Hall to part ways with the company. Within a month of leaving, he had purchased a controlling interest in a local flight school and transformed it into the Springfield Aircraft Company.

Springfield Aircraft Company (1931–1932)

By late 1931, Hall had moved his new company from Springfield Airport to Bowles-Agawam Airport across the Connecticut River. It was there that he would design and build his most personal creation: the Hall Bulldog.

In the spring of 1932, New York socialite and pilot Russell Thaw approached Hall with backing from Marron Price Guggenheim. They wanted the designer of the championship-winning Gee Bee Z to build them a Thompson Trophy contender.

Hall’s design was distinctive—a gull-winged monoplane powered by a specialized Pratt & Whitney Wasp T3D1 producing 730 horsepower. The aircraft was completed on August 15, 1932, just in time for the National Air Races. Mrs. Guggenheim named it “Bulldog” after her husband’s Yale mascot, despite the aircraft being painted in Harvard crimson.

The Bulldog qualified at an impressive 244 mph, with a peak speed of 271 mph recorded during testing. Russell Thaw piloted the Bulldog in the Thompson Trophy Race, but problems with the experimental Hamilton Standard controllable-pitch propeller limited engine performance, and the aircraft finished sixth at 216 mph.

Tragedy struck on December 4, 1932, when test pilot Frank Lynch was killed in a crash. Hall closed the Springfield Aircraft Company shortly thereafter, ending his independent aircraft manufacturing venture.

Stinson Aircraft (1933–1937)

After the closure of Springfield Aircraft, Hall joined Stinson Aircraft in 1933 as Chief Engineer of the transport division. During his four years at Stinson, he contributed to the development of the Stinson Model A and SR series aircraft—a marked departure from the high-speed racers that had made his reputation.

This period at Stinson gave Hall extensive experience with practical, production aircraft design. The skills he developed there—balancing performance with reliability, manufacturability, and cost—would prove invaluable in his next position.

Grumman: Designing the Arsenal of Democracy (1937–1970)

In 1937, Hall joined the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation at Bethpage, Long Island, New York as assistant chief engineer for experimental aircraft. Working alongside company founder Leroy Grumman and chief engineer Bill Schwendler, Hall would spend the next 34 years designing aircraft that became the backbone of American naval aviation. True to his principles, he also served as chief test pilot, personally making the first flight of nearly every prototype he designed.

World War II Fighters

Hall’s designs for Grumman read like a roster of aviation legends:

| Aircraft | Role | First Flight | Hall Test Flew |

|---|---|---|---|

| XF4F-3 Wildcat | Fighter | Sept 2, 1937 | Yes |

| XF5F-1 Skyrocket | Twin-engine Fighter | April 1, 1940 | Yes |

| XP-50 | Army Fighter | Feb 18, 1941 | Yes |

| XTBF-1 Avenger | Torpedo Bomber | Aug 1, 1941 | Yes |

| XF6F-1 Hellcat | Fighter | June 26, 1942 | Yes |

| XF7F-1 Tigercat | Twin-engine Fighter | November 1943 | Yes |

| XF8F-1 Bearcat | Fighter | August 1944 | Yes |

The test flights were not without drama. On one early Wildcat flight, the throttle stuck at full power. Hall calmly flew the aircraft until it ran out of fuel, then dead-sticked it to a safe landing. During an F6F Hellcat test flight, he narrowly avoided a mid-air collision with a young Navy ensign who wandered into restricted airspace.

The F6F Hellcat deserves special mention. Hall personally made the first flight of the prototype on June 26, 1942, at the Grumman plant in Bethpage. The Hellcat went on to achieve a 19:1 kill ratio against Japanese aircraft and is credited with destroying more enemy planes than any other Allied aircraft.

The Jet Age

As Grumman transitioned to jet aircraft, Hall continued to lead the engineering efforts:

- F9F Panther — Grumman’s first jet fighter

- F9F Cougar — Swept-wing development of the Panther

- F10F Jaguar — Variable-sweep wing experimental fighter

- F11F Tiger — Supersonic fighter

- Gulfstream I — Pioneering business turboprop

By this time, Hall had risen to Vice President of Engineering. It was during the F9F Panther program that Grumman management finally insisted he stop personally test-flying the prototypes—he had become too valuable to risk losing.

A Test Pilot’s Philosophy

April 1940 Velvet tobacco advertisement: “Aeronautical engineer who tests and perfects some of the Navy’s finest planes”

Tydol Flying A advertisement featuring “R.L. Bob Hall, Chief Test Pilot, Grumman Aircraft”

Throughout his career, Hall maintained a remarkable principle: he refused to let anyone else take the risk of flying his designs until he had done so himself. This wasn’t ego—it was integrity. He believed that if he was going to ask military pilots to trust their lives to his aircraft, he should be willing to do the same.

This philosophy made him a celebrity in his era. National advertisements featured Hall as the face of American aviation excellence, from tobacco to gasoline. These ads emphasized his dual role as both designer and test pilot—a combination that was becoming increasingly rare as aircraft grew more complex.

Legacy and Family

Bob Hall retired from Grumman in 1970 after 34 years with the company. He had risen from assistant chief engineer to Vice President of Engineering, overseeing the design of aircraft that helped win World War II and establish American dominance in naval aviation during the Cold War.

His legacy extended beyond his own achievements. Two of his sons, Eric and Ben Hall, founded Hall Spars and Rigging in Bristol, Rhode Island, carrying on their father’s tradition of precision engineering.

Robert Leicester Hall died on February 25, 1991, in Newport, Rhode Island, at the age of 85. He left behind a legacy of innovation, integrity, and an uncompromising commitment to excellence that influenced generations of aerospace engineers.

Life Timeline